Crosby, Stills & Nash Revisit “Long Time Gone” With Undiminished Urgency on the 2012 Tour

During their 2012 tour, Crosby, Stills & Nash delivered a powerful reminder of why their music continues to resonate across generations, none more striking than their live performance of “Long Time Gone.” Originally written by David Crosby in 1969 at the height of political and social unrest in the United States, the song reemerged more than four decades later with a renewed sense of relevance and gravity.

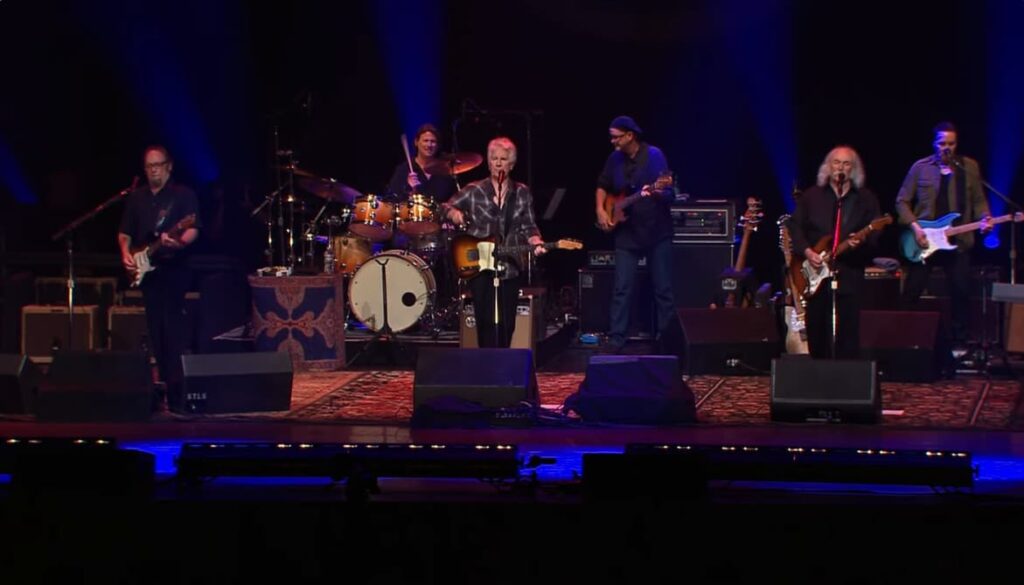

By 2012, David Crosby, Stephen Stills, and Graham Nash were no longer the young voices of a restless generation, but seasoned artists carrying the weight of history in their performances. That maturity gave “Long Time Gone” a different kind of authority. The urgency was no longer youthful defiance, but a reflective warning shaped by experience. Crosby’s vocal delivery retained its edge, sharp and uncompromising, while Stills anchored the song with tightly controlled guitar work that emphasized tension rather than flash. Nash’s harmonies provided balance, reinforcing the signature CSN sound that remains instantly recognizable.

What made the 2012 live rendition particularly compelling was its restraint. Rather than reworking the song to chase nostalgia, CSN allowed it to breathe within a lean arrangement. The performance avoided excess, letting the song’s message stand on its own. In an era still marked by political division and global uncertainty, the lyrics felt unsettlingly current, proving that “Long Time Gone” had lost none of its relevance.

Audience reaction during the tour reflected that enduring power. Longtime fans recognized the song as a cornerstone of CSN’s catalog, while newer listeners encountered it as a timely statement rather than a historical artifact. The performance underscored that Crosby, Stills & Nash were not merely revisiting past glories, but reaffirming their role as artists willing to confront uncomfortable truths.

Within the context of the 2012 tour, “Long Time Gone” stood out as more than a setlist staple. It was a statement of continuity, linking the social consciousness of the late 1960s to the realities of the modern world. In revisiting the song with clarity and conviction, Crosby, Stills & Nash demonstrated that their legacy is not defined solely by harmony and melody, but by a willingness to speak plainly, even decades after the song was first written.