The Cynical Weaponization of Sentimentality: A Drama of Betrayal, Obsession, and a Subtle, Brilliant Jab at Rock’s Biggest Hitmakers.

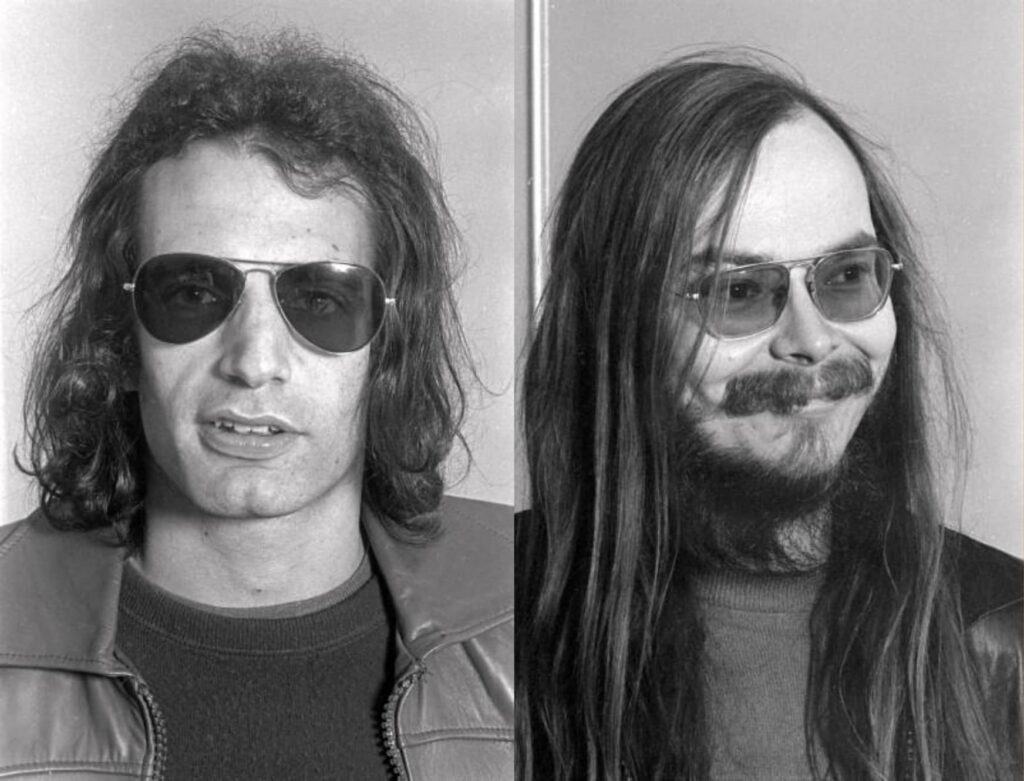

The world of 1976 was a high-gloss, cynical landscape, perfectly captured by the master ironists Donald Fagen and Walter Becker on the Steely Dan masterpiece, The Royal Scam. While the album itself—a dense, jazzy funk exploration of losers, criminals, and the rot beneath the American Dream—was a commercial success, reaching No. 15 on the US Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart, it was never a conveyor belt of hit singles. Tracks like the sleek, venomous “Everything You Did” were album cuts, a subtle form of sophisticated poison designed to sink deep into the listener, not top the pop charts. As such, “Everything You Did” was never released as a single and has no individual chart position, existing as an essential, moody piece of a larger, dramatic whole.

Key information: The song “Everything You Did” is an album track from Steely Dan’s 1976 album, The Royal Scam. The album peaked at No. 15 on the US Billboard Top LPs & Tape chart and was certified Platinum. The song is a brutal, dialogue-driven exploration of a relationship shattered by betrayal. Its most famous lyric, “Turn up the Eagles, the neighbors are listening,” is a deliberate, witty taunt aimed at their contemporary rivals, The Eagles, a shot that was soon returned on The Eagles’ monumental 1976 album, Hotel California.

The story behind this track is a tale of domestic warfare and artistic one-upmanship, played out in the claustrophobic confines of a West Coast apartment. Fagen and Becker, always more interested in crafting complex, fictional narratives than their own feelings, set the scene of a husband confronting his cheating wife. The mood is not one of heartbroken ballads, but of cold, calculating interrogation, punctuated by the song’s frantic, quasi-reggae beat and Larry Carlton’s sharp, unforgiving guitar solo. The narrator, driven less by pain and more by a terrifying, obsessive need for detail, demands the woman “do me everything you did,” a demand that is both sexually charged and psychologically torturous. It is a terrifying window into a love that has curdled into a dark form of control.

But for the well-informed listener of the era, the true drama and eternal smirk of Steely Dan arrived in a single, throwaway line of dialogue: “Turn up the Eagles, the neighbors are listening.” This was a meta-narrative blast aimed directly at the heart of their shared manager’s other massive band, The Eagles. It was the ultimate, condescending dismissal—the idea that the cheating couple needed to drown out the noise of their fight with the sonic equivalent of background music, the soft-rock comfort food that was the easy-listening Eagles. This line, a rumored jibe from Becker about his girlfriend’s affection for the band’s more accessible, stadium-friendly sound, was the sound of the ultimate music snob mocking the ultimate crowd-pleaser.

The glorious retort came later that same year on The Eagles’ album, Hotel California. In the chilling title track, Don Henley and Glenn Frey—men who knew a good literary feud when they saw one—fired back with the unforgettable, cryptic line: “They stab it with their steely knives, but they just can’t kill the beast.” This was no mere coincidence; Frey himself confirmed it was a playful nod back to Steely Dan, acknowledging the rivalry while asserting their own band’s unkillable dominance on the airwaves.

The meaning of “Everything You Did” thus expands beyond a dark domestic tragedy. It became a piece of rock history’s most brilliant, passive-aggressive dialogue—a whisper of rivalry between the cerebral jazz-rock gods and the chart-busting cowboys. It speaks to an era when rock-and-roll was less a genre and more a sophisticated, dramatic battleground, where the most vicious feuds were fought not with fists, but with a perfectly placed, devastatingly witty lyric. For those of us who lived through the seventies, this back-and-forth—the snide joke in the living room and the epic return volley from the Hotel lobby—is a nostalgic reminder of rock’s golden age of complex genius and high-stakes drama.