A Fiery, Apocalyptic Reinterpretation of an Allegorical Masterpiece: The Jimi Hendrix Experience’s Cover of “All Along the Watchtower” is the Rare Instance Where the Pupil Overtakes the Master, Transforming a Folk Lament into an Electric-Charged Prophecy of Doom and Liberation.

There are moments in music history that don’t just mark a point in time, but irrevocably change the course of the very river they inhabit. The release of The Jimi Hendrix Experience‘s seismic cover of Bob Dylan‘s “All Along the Watchtower” in September 1968 was one such moment. For those of us who lived through the tumultuous late sixties, this song wasn’t merely a chart hit; it was the soundtrack to a world on the brink, a terrifyingly beautiful roar of electric rebellion that perfectly encapsulated the chaotic energy of the era.

Upon its release as a single, the track, featured on the sprawling double-album magnum opus, Electric Ladyland (1968), soared up the charts, becoming Jimi Hendrix‘s biggest-selling single in the United States, peaking at Number 20 on the Billboard Hot 100. Across the Atlantic, the song achieved an even greater commercial triumph, hitting Number 5 on the UK Singles Chart. The parent album itself was a landmark, becoming The Jimi Hendrix Experience‘s only chart-topping album in the US, where it reached Number 1 on the Billboard Top LPs chart. Yet, its true impact was measured not in numbers, but in the sheer, visceral shockwave it sent through popular music.

To understand the sheer audacity of Hendrix’s rendition, one must first recall Dylan’s original: a spare, acoustic lament from his 1967 album, John Wesley Harding. It was a cryptic, Biblical-tinged allegory, full of unsettling quietude, depicting a stark dialogue between a “Joker” and a “Thief” discussing an impending apocalypse or paradigm shift from the confines of a prison-like tower. Dylan offered a parable that hinted at the end of the established order—the princes, the ploughmen, the women, and the watchmen—all swept aside by a storm. The mood was somber, prophetic, and deeply poetic.

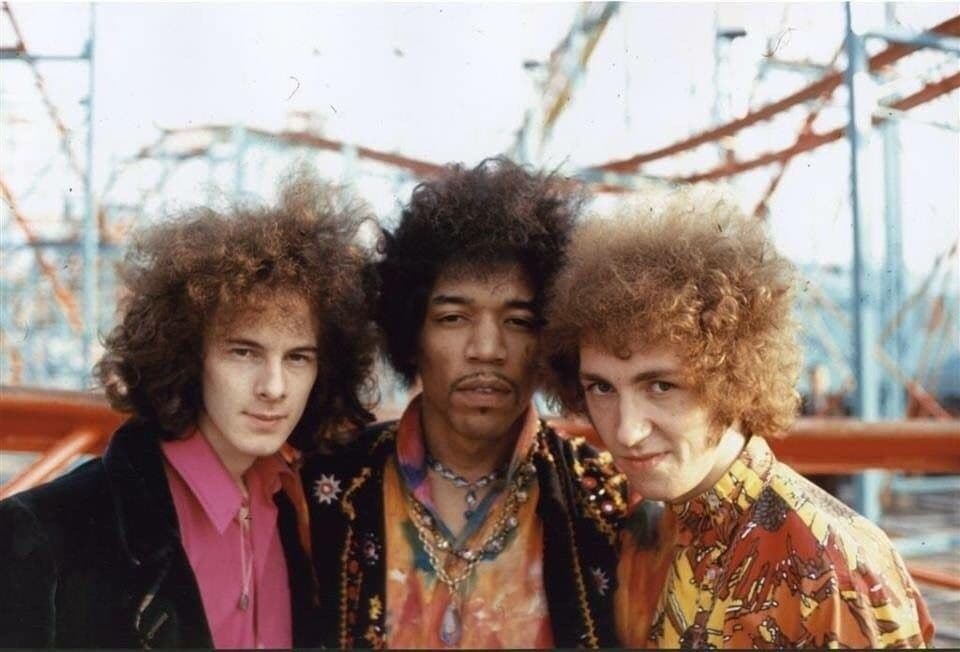

But when the cassette of Dylan‘s work found its way into Jimi Hendrix‘s hands, the song’s delicate tapestry was instantly set ablaze. The story goes that Hendrix was immediately captivated by the lyrics, carrying Dylan‘s album with him, feeling the apocalyptic urgency in the words. He didn’t just cover it; he possessed it. What followed in the legendary Olympic Studios in London was a torturous, yet ultimately triumphant, recording process, stretching over dozens of takes and featuring a rotating cast of musician friends, including Dave Mason of Traffic and even an uncredited Brian Jones of The Rolling Stones. The final result—a triumph of multitrack layering, swirling with backwards tape effects, flanging, and three distinct, searing guitar solos—was pure rock-and-roll drama.

The heart of “All Along the Watchtower” remains its dark, allegorical meaning: a stark confrontation with fate, a commentary on societal values, and an impending doom. The “Joker” laments that “There’s too much confusion, I can’t get no relief,” and the “Thief” responds with hard-won wisdom, urging honesty, as “the hour’s getting late.” For those living through the Vietnam War, the counterculture revolution, and the assassinations that shook the 1960s to its core, this was not ancient scripture; it was a dispatch from the present. Hendrix’s searing guitar work, which evokes the sound of two riders—like the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, perhaps—approaching in a dusty, gathering storm, transformed the song’s cryptic dread into a full-blown, psychedelic conflagration. It was the sound of a world exploding, then being born anew.

It is a rare, cherished phenomenon when an artist can take a masterpiece by another and elevate it to an entirely new spiritual and artistic plane. Hendrix’s “All Along the Watchtower” achieved this feat so thoroughly that Bob Dylan himself, in a profound gesture of artistic surrender, would later admit that he began performing the song in Hendrix‘s arrangement, stating it was often a tribute to the guitarist’s genius. This isn’t just a song; it’s a monumental cultural transfer, a visceral memory of a time when a single chord could feel like a call to revolution, and when the electric guitar, in the hands of a true poet, became the sound of destiny itself.