A Rebel’s Quest for Identity: Slade’s “Know Who You Are”

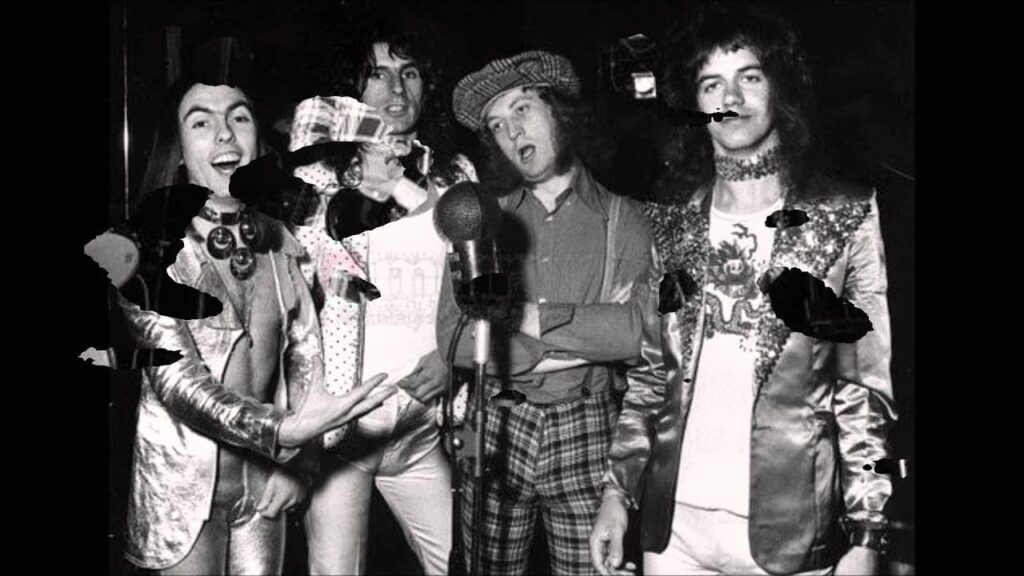

In the restless autumn of 1970, Slade, the Wolverhampton warriors of rock, unleashed “Know Who You Are”, a single that stumbled shy of the UK charts, released on September 18 by Polydor Records. Pulled from their second album, Play It Loud, which itself failed to dent the Top 40, this track marked a gritty pivot for Noddy Holder, Jim Lea, Dave Hill, and Don Powell—a band still clawing for footing after their skinhead reinvention. For those of us who roamed the early ‘70s, when the air thrummed with change and rock was a raw, unpolished howl, this song is a faded Polaroid—a restless anthem of self-discovery, a shout into the void of a world that hadn’t yet caught up. It’s the sound of boots on cobblestones, of dreams too big for small towns, tugging at the soul of anyone who ever stood at life’s crossroads, wondering who they’d become.

The birth of “Know Who You Are” is a tale of grit and gamble. By 1970, Slade were in flux—their 1969 debut Beginnings (as Ambrose Slade) had flopped, and manager Chas Chandler, ex-Animals bassist, was steering them hard. He’d pushed them to ditch Fontana for Polydor, shed their old sound, and write their own fate. Recorded at Olympic Studios in London, the song evolved from their instrumental “Genesis,” with Holder and Lea layering lyrics over its bones—a restless riff born of late-night jams. It was their Polydor debut, a bold swing after two failed singles, but the skinhead image they’d adopted didn’t click with the masses yet. Holder later recalled the sting: “We’d been slogging for two years with Chas, and still no hit.” The track’s failure stung, but its live version on 1972’s Slade Alive! and its inclusion on 1973’s chart-topping Sladest later proved its worth, turning a collector’s rarity—valued at £80 by 2014—into a cult echo of their pre-glam days.

At its heart, “Know Who You Are” is a raw, urgent plea to seize your own story—a rebel’s cry against the grind. “Know who you are, know where you’re going to,” Holder snarls, his voice a jagged edge over Lea’s bass pulse, “Just take a look at the things that make up a good living.” It’s a young man’s manifesto—trying on his father’s shoes, running wild, chasing answers: “Read a new book, finish the other one, right from the start try and work out the finishing answer.” For older listeners, it’s a portal to those ‘70s streets—skinhead crews, transistor radios, the ache of finding yourself amid the noise. It’s the flicker of a pub’s dim lights, the rush of a motorbike’s roar, the moment you dared to dream beyond the factory gates. As the final “sing a song” fades, you’re left with a quiet fire—a nostalgia for when every chord was a question, and knowing who you were felt like the fight of your life.