A Rebel’s Toast to Fate and Folly: Thin Lizzy’s “Whiskey in the Jar”

In the crisp autumn of 1972, Thin Lizzy, Ireland’s hard-rock poets, unleashed their rendition of “Whiskey in the Jar”, a single that stormed to #6 on the UK Singles Chart and lingered for 17 weeks, released on November 3 by Decca Records. Though not on a studio album—it later appeared on 1974’s Vagabonds of the Western World deluxe editions—this reimagining of a traditional Irish folk tune became their breakout hit, selling over a million copies worldwide. For those of us who roamed the early ‘70s, when rock carried a Celtic lilt and the air thrummed with defiance, this song is a battered tin mug—a tale of rogues and betrayal, a memory of nights when the bottle was both friend and foe. It’s the sound of a pub singalong turned electric, tugging at the soul of anyone who’s ever raised a glass to a lost cause.

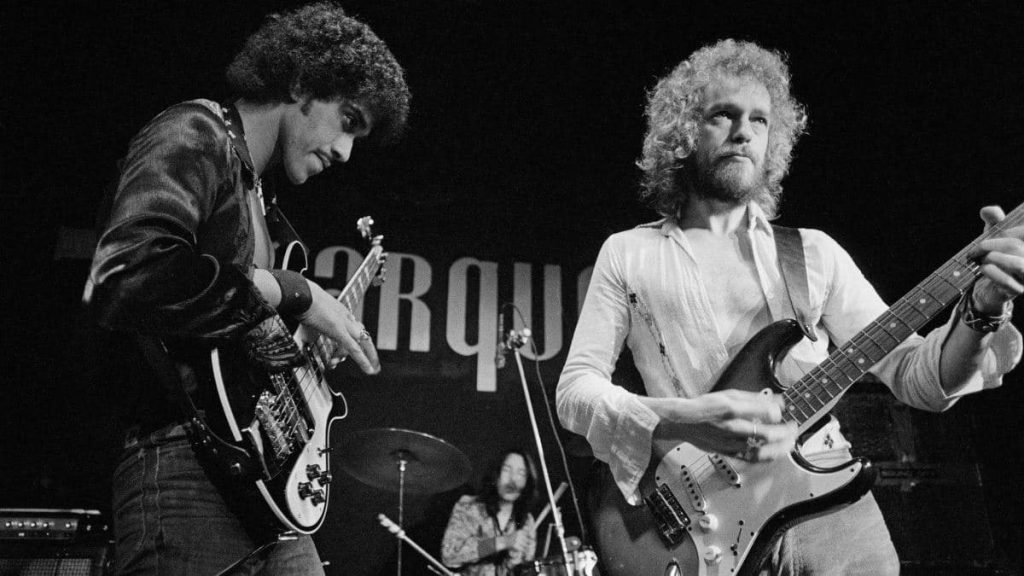

The story behind “Whiskey in the Jar” is a blend of chance and alchemy. By late 1972, Thin Lizzy—Phil Lynott, Eric Bell, and Brian Downey—were a trio teetering on the edge, their first two albums (Thin Lizzy and Shades of a Blue Orphanage) barely rippling the charts. Jamming in a London pub, Bell suggested the old folk song—about a highwayman betrayed by his lover—after hearing it from The Dubliners. Lynott, Dublin’s streetwise bard, seized it, electrifying its reels with his soulful growl and a riff that danced like a jig on fire. Recorded at Decca’s Tollington Park Studios with producer Nick Tauber, it was a fluke single—meant as a B-side until radio grabbed it. Bell’s chiming guitar solo, Downey’s rolling drums, and Lynott’s “musha ring dum a doo” nod to tradition turned a lark into a legend. Released as glam glittered and prog loomed, it was their lifeline—propelling them from dives to Top of the Pops, though Bell quit a year later, weary of the grind.

At its heart, “Whiskey in the Jar” is a rollicking lament—a rogue’s tale of love and doom. “I took all of his money and it was a pretty penny,” Lynott sings, his voice a roguish grin over Bell’s lilting strings, “But me and my pistol, we parted the next day / When Molly drew her pistol, my God, she did betray.” It’s a highwayman undone—“There’s whiskey in the jar-o”—jailed yet defiant: “If anyone can aid me, ’tis my brother in the army.” For older listeners, it’s a portal to those ‘70s nights—spilling from gigs into foggy streets, the air thick with stout and swagger, the rush of a yarn spun loud. It’s the clink of a glass on a bar, the sway of a leather jacket, the moment you cheered for the outlaw. As the final “whack fol de daddy-o” rings out, you’re left with a rugged glow—a nostalgia for when every chord was a dare, and whiskey fueled the sweetest rebellion.