A Raw and Unflinching Confession of Addiction’s Grip, Spontaneously Captured in the Sterile Heart of the American Road.

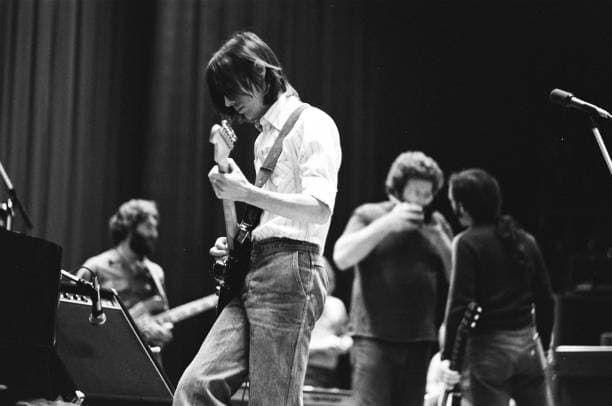

By 1977, Jackson Browne was the undisputed poet laureate of the Southern California singer-songwriter movement, yet his songs were increasingly infused with the disillusionment and relentless exhaustion of the road. His album Running on Empty was a radical concept—a raw, unvarnished document of touring life, recorded in limousines, on stage, and in hotel rooms. The album was a massive commercial success, peaking at number 2 on the Billboard 200 and establishing a new benchmark for rock authenticity. Among its spontaneous brilliance was a track that, while relegated to the B-side of the smash hit “Running on Empty” (which peaked at No. 11 on the Hot 100), became an instant, haunting classic. That song was “Cocaine.” The true drama of this track, however, is inseparable from its legendary point of origin: it was recorded in the mundane, standardized reality of Room 124, Holiday Inn, Edwardsville, Illinois, on August 17, 1977.

The story behind this recording is the stuff of rock and roll mythology, a perfect reflection of the mid-to-late 1970s scene where the lines between the personal and the public were constantly blurred. The stark contrast between the sterile, generic setting of a roadside Holiday Inn room and the dark, raw subject matter of the song is the essence of its dramatic power. This wasn’t a pristine studio recording; it was a spontaneous moment of truth, captured on a portable recorder during a tour stop. Browne reached back to the deep blues tradition, taking the framework of the classic folk song popularized by Reverend Gary Davis, and updated it for the excesses of the modern rock era. The added lyrics, co-written with his close friend Glenn Frey of The Eagles (a testament to the tightly woven, collaborative drama of the L.A. music community), gave the old tale a contemporary, chilling resonance. It feels less like a performance and more like a weary confession shared after a long night, an honest acknowledgment of the shadow that followed the industry everywhere.

The meaning of “Cocaine” is stark, simple, and utterly tragic: it is a raw, unflinching look at the seductive, mesmerizing, and ultimately destructive grip of addiction. The “drama” is in the narrator’s resigned acceptance of his fate. The lyrics do not celebrate the drug; they lament the obsession, painting a portrait of a soul caught in a self-destructive cycle. The recurring refrain, “Cocaine, running all ’round my brain,” is not a joyful shout, but a profound, weary groan of surrender. Browne’s delivery, backed only by his simple acoustic guitar and a haunting harmonica, strips away the glamor, leaving only the desolate honesty of the blues. The musical choice to keep the arrangement simple and acoustic emphasizes the timeless nature of the addiction narrative, proving that the struggle against internal demons is as old as the hills.

For those of us who came of age during this era, “Cocaine” is more than an album track; it’s a visceral memory. It’s a nostalgic trip back to a time when the mythology of the road was at its peak, and when rock artists had the artistic courage to document the harder truths of their lives without filtering. It stands as a timeless and deeply emotional piece of music, a perfect document of the quiet desperation and profound drama that lurked just beyond the stadium lights.