A Moment of Transcendence in the Midst of Glamour and Despair

“Time Out of Mind” by Steely Dan, from their sleek, labyrinthine album Gaucho (1980), is a quietly devastating meditation that climbed to #22 on the U.S. Billboard Hot 100.

In the shimmering, meticulously produced world of Gaucho, Steely Dan’s sixth studio single stands out as a rare burst of raw, emotional release. Beneath its polished veneer lies a deeply personal and unsettling tale—a song that, while carried on a veneer of warm jazz-pop, speaks of escapism, addiction, and the illusory promise of transcendence.

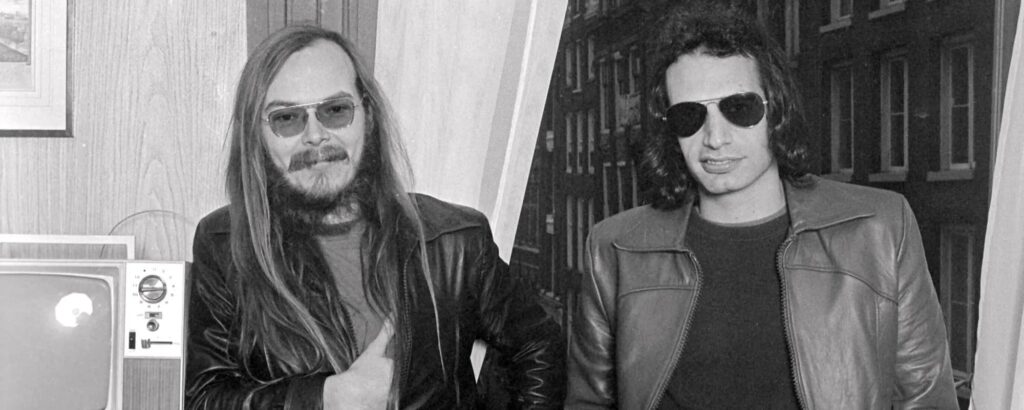

Written by Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, “Time Out of Mind” traces a young man’s initiation into the dark undercurrents of heroin use. The opening lines offer a father’s cautionary blessing—”Son you better be ready for love on this glory day”—but soon give way to a surreal journey: “Tonight when I chase the dragon,” he sings, invoking a well-known metaphor for pursuing heroin’s euphoric high. Water transmutes into “cherry wine,” silver into gold—a transformative alchemy born of chemical escape. The song’s dreamlike imagery continues with a “mystical sphere direct from Lhasa,” a possible allusion to Tibetan opium traditions and the exoticism that often lures in those seeking more than the humdrum of everyday life.

Musically, “Time Out of Mind” is deceptively buoyant. It’s set in A major, modulating to D major in the chorus, and built around three interlocking riffs, giving the arrangement both forward motion and a hypnotic pull. The groove is soulful and poised, a static strut that belies the recklessness hidden beneath the surface. On top of that, Steely Dan’s exacting production—the same precision that defined Gaucho—carves space for guest singing from Michael McDonald, whose warm backing vocal in the pre-chorus sounds like a weary exhale.

But even as the music soothes, the lyrics unsettle. Critics like those at Stylus Magazine have read the song as “a wry testament to the incredible feeling of feeling nothing at all,” highlighting how the instrumental brightness belies a narrative of self-annihilation. Retrospective commentators echo this: Stephen Thomas Erlewine calls the track “suave” in contrast to the rest of Gaucho’s glossy, wandering fusion.

In the larger context of Gaucho, the song becomes part of a sharply observed world of aspirational hipsters, disillusionment, and existential surrender. Steely Dan never frame their characters in grand tragedy; rather, they sidle close, noting details with both affection and clinical clarity. “Time Out of Mind” feels like a private confession, caught between synthetic sophistication and emotional ruins.

For listeners, the emotional impact is profound. It is not a sensationalized ode to drug use, but a lament—a hymn to the seductive power of escape, and the dangerous beauty in chasing something that promises to suspend time. The phrase “time out of mind” itself captures the core paradox: a longing for a timeless, perfect realm, even as the boundaries of reality fray.

In hindsight, the song resonates as one of Walter Becker and Donald Fagen’s most vulnerable pieces—a poignant stop on the final album they made together before a two-decade hiatus. “Time Out of Mind” is both elegy and invocation: an elegy for innocence, and an invocation of transcendence, however fleeting or fatal.