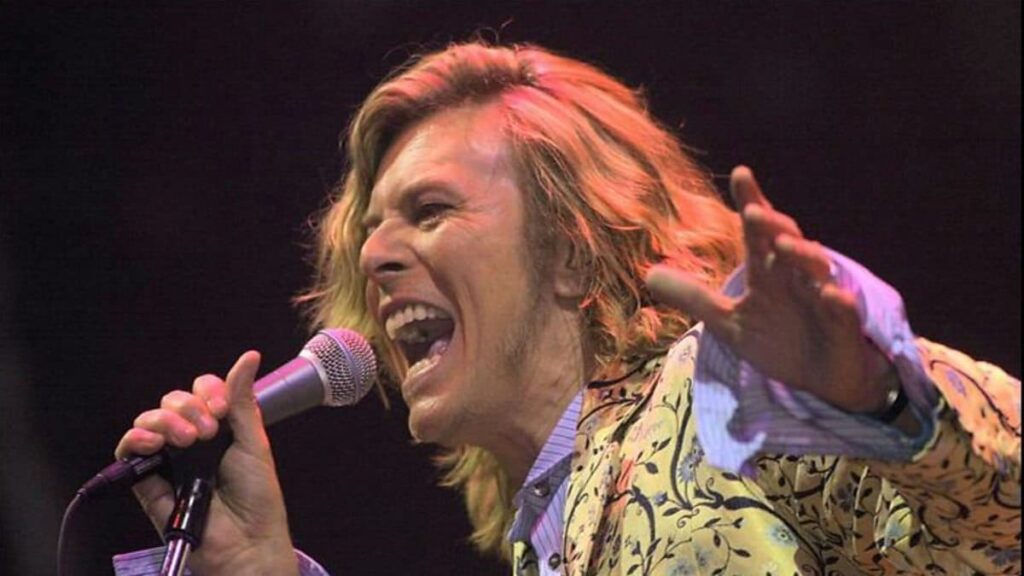

David Bowie

A haunted conversation with the self, reborn onstage with quiet fire and spectral clarity

When David Bowie performed “The Man Who Sold the World” during his 2000 BBC Radio Theatre concert, later included on releases connected to his live work of that era, he revisited one of the most enigmatic songs from his early career. Originally the title track of his 1970 album The Man Who Sold the World, the song was never a major chart entry in its original form, yet it grew steadily in cultural weight, eventually becoming one of his most studied and mythologized compositions. By the time Bowie reached that intimate stage in 2000, the piece had already lived many lives, including a surge of renewed attention in the 1990s after its prominent reinterpretation elsewhere. Bowie’s own live version in 2000 stands as a reclamation, a thoughtful return to a work that had shadowed him for decades.

What makes this performance compelling is not its volume or theatricality but its restraint. Bowie sings with a voice seasoned by years of reinvention, shaped by triumphs and crises, mellowed by age yet sharpened by understanding. Instead of leaning into the darker, electrified tension of the 1970 studio recording, he delivers something quieter, more introspective, even confessional. The arrangement feels tighter and more acoustic, letting the song’s core themes rise to the surface without distraction.

At its heart, “The Man Who Sold the World” is an inquiry into identity, alienation, and the uncanny sensation of meeting another version of oneself. Bowie once crafted personas like shifting masks, exploring the instability of identity long before pop culture embraced the concept. In this performance, however, the song feels stripped of character play. It is not Ziggy, nor the Thin White Duke, nor any other persona. It is Bowie as a man in his fifties, looking back at the younger self who once wrote about the fractured mind and the slippery nature of selfhood. The dialogue within the lyrics, where one encounters a double and grapples with forgotten or abandoned parts of the soul, resonates differently when sung by an artist who spent decades inventing and shedding identities.

Musically, the 2000 live version reveals the song’s bones. The melody floats with a gentle sadness, and the rhythmic approach places emphasis not on drama but on the inevitability of the meeting described in the lyrics. The phrasing feels more reflective, less theatrical. Bowie leans into the weariness between the lines, drawing out the mystery rather than amplifying it.

There is a sense of closure intertwined with renewal. On that BBC stage, Bowie revisits the puzzle of the self, but now with the calm acceptance of someone who has walked through his own labyrinth and emerged wiser. The performance becomes not only a reinterpretation but a conversation across time, an artist acknowledging the ghosts of his past while singing with the clarity of a man who finally understands them.