A sharp portrait of ambition, success and the quiet emptiness that waits at the top

When Roger McGuinn released King of the Hill as the lead single from his 1991 album Back from Rio, it became a late career standout, climbing to No. 2 on the U.S. Mainstream Rock chart and reintroducing him to a new generation of listeners. The album itself marked a creative resurgence, bridging his folk rock legacy with a modern, polished rock sound. At the center of that revival sits this song, a track that is equal parts critique, confession and cautionary tale.

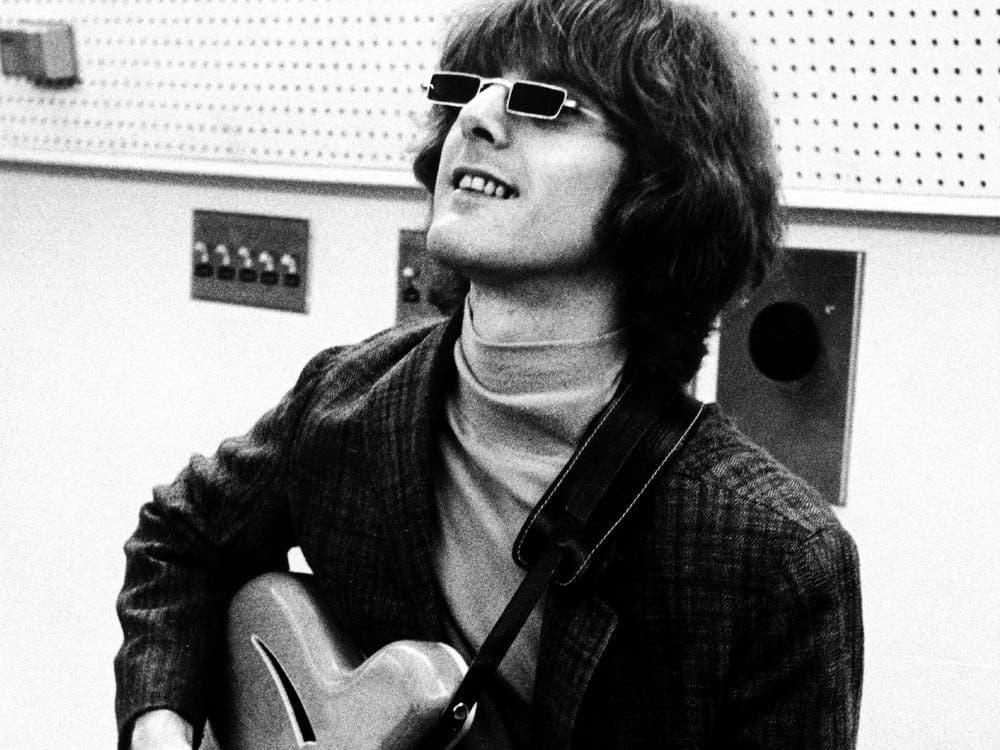

From its opening seconds, the song carries a restless pulse. The guitars shimmer with McGuinn’s unmistakable 12 string sparkle, yet the tone is sharper and more grounded than his psychedelic folk past. Members of Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers contribute to the recording, giving the song a muscular presence that feels both contemporary and deeply connected to McGuinn’s roots. The performance has a sense of urgency, as if the music is pushing forward while the lyrics try to pull back the curtain on what that forward motion costs.

Lyrically, King of the Hill tells the story of someone who has reached a place society labels as success. There is wealth, prestige, a home perched above the world and the careful symbolism of curated luxury. Yet every image is undercut by a shadow. The glamorous house feels cold. The crowds gathered around the protagonist feel transactional rather than affectionate. Status, once desired, becomes a lonely burden. The crown on the king is heavy and quietly absurd.

There is a moral gravity to the writing. The song does not mock ambition, nor does it glorify it. Instead, it observes. It studies the hollowness that can appear when outward achievement replaces inner fulfillment. The imagery of broken glass, fading lights and whispered warning turns success into something brittle. The king stands tall, but the world beneath his feet feels unstable.

Musically, the track is a bridge between eras. It preserves the poetic clarity and jangling textures that defined McGuinn’s work with The Byrds, yet it is dressed in the tone and production of early 1990s adult rock. The sound is confident, polished and mature, a reminder that reinvention can be subtle rather than explosive.

Today, King of the Hill endures as one of McGuinn’s most thoughtful later period recordings. It speaks to anyone who has ever chased a dream only to discover that arrival does not guarantee meaning. It is a reminder that the summit can be quiet, lonely and oddly fragile and that sometimes the cost of the climb is realizing how much of yourself you left behind on the way up.