A darkly funny confession wrapped in jazz-shaded cynicism about guilt, consequence, and the strange fragility of human behavior

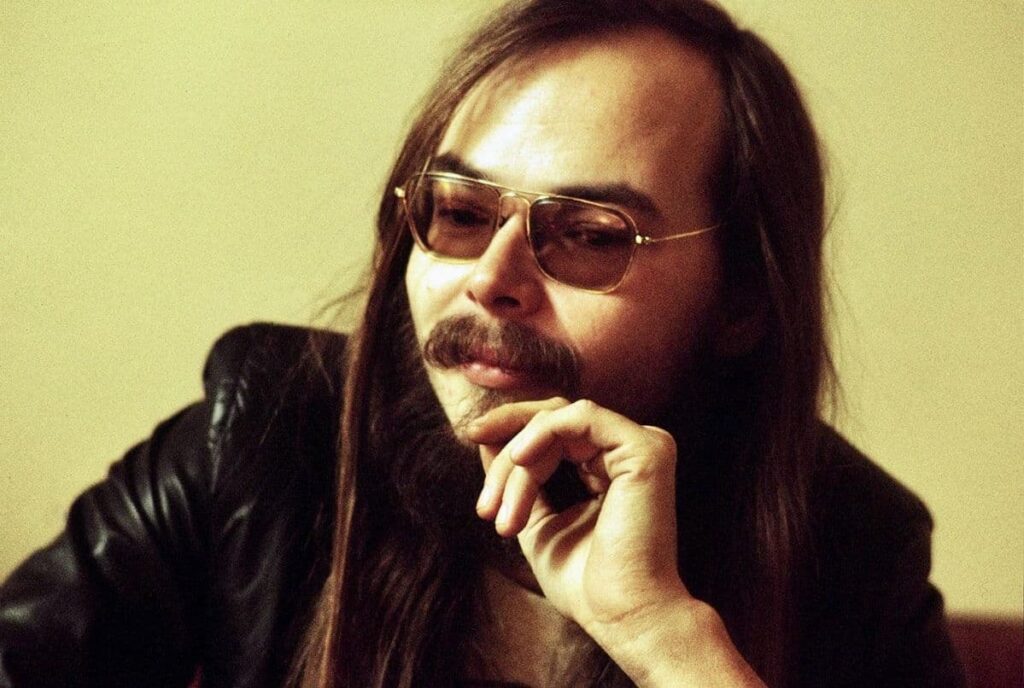

When Walter Becker delivered what fans now refer to as “The Prison Story”, captured almost by accident while the tape was rolling and the band played loose atmospheric backing behind him, something rare happened. The moment blurred the line between performance and private thought. There was no chart placement, no album single, no commercial intent. Instead, it lived as one of those intimate Steely Dan adjacent artifacts where Becker, often the quieter half of the partnership, let his mind wander out loud. Someone flipped the record switch, the tape began turning, and what emerged was a spoken monologue that felt both improvised and strangely precise, as if he had been holding those words for years.

Listening to it, one realizes how deeply Becker’s storytelling voice reflected the essence of the Steely Dan worldview. Beneath the deadpan delivery sits a kind of weary intelligence, the sense that moral certainty is an illusion and every person, if pushed far enough, becomes a character in one of life’s darker punchlines. In this monologue, Becker leans into themes that run through his songwriting with Donald Fagen: crime, punishment, regret, the absurdity of authority, and the uncomfortable humor that sits between sin and consequence. It feels like a man both confessing and observing, as if he cannot quite decide whether he is inside the cell or studying it from a safe academic distance.

What stands out most is the pacing. Becker never rushes the story. The background music sets a late-night mood, something smoky and unhurried, the kind of sound that belongs in a bar where the lights are low and no one asks questions. His voice enters almost reluctantly, filled with reflective pauses, the hesitations of someone explaining the unexplainable. There is weight in his tone, but also mischief. Every sentence walks a thin line between tragedy and comedy. That duality was always one of Steely Dan’s greatest weapons.

The monologue’s imagery lingers. You can hear the walls, the fluorescent hum, the institutional monotony. Yet Becker never begs sympathy. Instead, he treats the experience with his signature detachment, turning what could have been a confessional into a philosophical satire. The listener cannot help wondering whether the story is literal, metaphorical, exaggerated, or none of the above. That ambiguity is its brilliance.

In the end, “The Prison Story” feels like a window into Becker’s private creative language. It is raw, strange, literary, and unmistakably his. More than anything, it reminds us that his genius was not only in songwriting but in the way he perceived the world: with sharp intelligence, a dry grin, and the understanding that sometimes the only sane response to darkness is to describe it beautifully.